By Eric Koch / Anefo – http://proxy.handle.net/10648/ab63599e-d0b4-102d-bcf8-003048976d84, CC0, Link

Remembering John Lennon – The music died for my generation with the December 8, 1980 assassination of the musical genius and peace activist.

For my parents’ generation, the 3rd of February of 1959 was, in the words of Don McLean, “The Day the Music Died” (from his song “American Pie” dedicated to the memory of Buddy Holly).

Nearly 22 years later, on the 8th of December of 1980, the music died for both their generation and my own with the mindless assassination of John Lennon.

I grew up with John Lennon: first with the Beatles providing the soundtrack for my early childhood and, later, Lennon’s solo work became in many ways the anthem of my adolescence.

Born in 1963, the son of two hippie university professors, my childhood was inexplicably interwoven with the music and passion of those four “Mop Tops” from Liverpool, England. However, if the music of the Beatles defined my early childhood, clearly, the passion and protests of John Lennon helped mold and shape the years leading into my adulthood.

As a child of the sixties, I was also a child of the Vietnam War. It was the first televised, or “Living Room War”, and was a daily part of my childhood. My parents were always interested in both national and foreign affairs: on weeknights, they would turn

on the evening news, and ghastly images of that war would fill the television screen for a few minutes, bringing that horrible war home to us… to me.

Unlike the footage of WWII, the film clips were not scrutinized or censored by the government, and I would sit in front of our old black and white Imperial Television purchased by my father years before while in college. To this day, black and white film footage of Vietnam conveys a stronger sense of the mindlessness of war than the color footage of my generation’s wars. One of the most poignant images of the war came in the midst of the Tet Offensive when a Viet Cong terrorist was captured by South Vietnamese military officials and was summarily executed in the streets of Saigon.

Towards the latter part of the sixties, two events stand out in my mind when thinking about the war. The first was Walter Cronkite’s unprecedented editorial statement on the CBS Evening News on February 27th of, 1968 when he declared:

[I]t seems now more certain than ever that the bloody experience of Vietnam is to end in a stalemate. This summer’s almost certain standoff will either end in real give-and-take negotiations or terrible escalation; and for every means we have to escalate, the enemy can match us, and that applies the invasion of the North, the use of nuclear weapons, or the mere commitment of one hundred, or two hundred, or three hundred thousand more American troops to the battle. And with each escalation, the world comes closer to the brink of cosmic disaster.

To say that we are closer to victory today is to believe, in the face of the evidence, the optimists who have been wrong in the past. To suggest we are on the edge of defeat is to yield to unreasonable pessimism. To say that we are mired in stalemate seems the only realistic, yet unsatisfactory, conclusion. On the off chance that military and political analysts are right, in the next few months we must test the enemy’s intentions, in case this is indeed his last big gasp before negotiations. But it is increasingly clear to this reporter that the only rational way out then will be to negotiate, not as victors, but as an honorable people who lived up to their pledge to defend democracy, and did the best they could.

After watching Cronkite’s broadcast, LBJ was quoted as saying. “That’s it. If I’ve lost Cronkite, I’ve lost middle America.”

The second defining event for me began in September of 1969 when, in protest of Great Britain’s support of the Vietnam War, John Lennon returned his MBE (Member of the British Empire), which had been awarded to the Beatles in 1965 by Queen Elizabeth. If Walter Cronkite had lost the support of “middle America” for the Vietnam War, this protest and subsequent anti-war efforts by John Lennon eventually lost its support from much of the rest of the world.

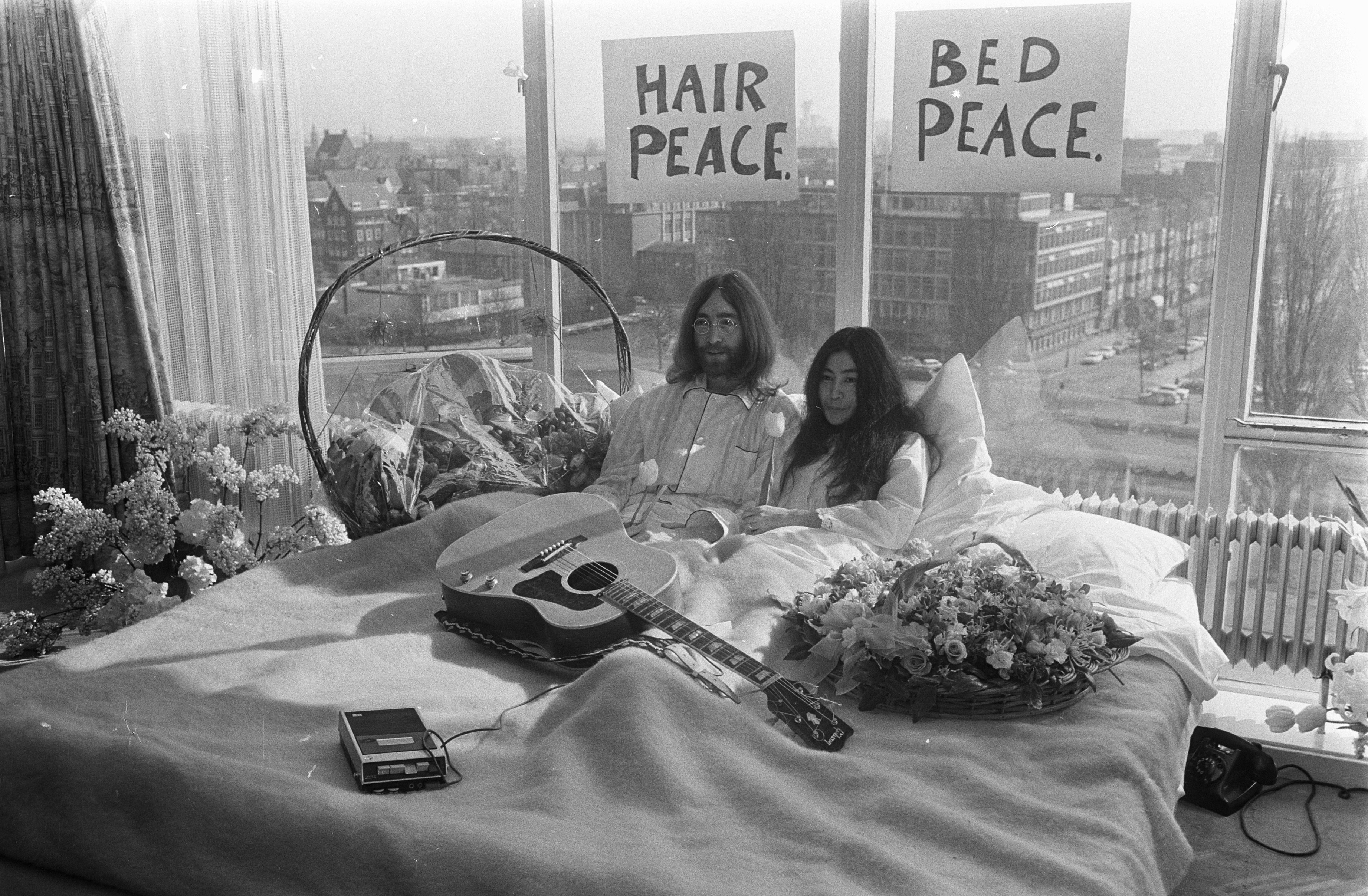

Over the course of the next few years, and to his own peril, John Lennon actively campaigned against the war. Shortly after his marriage to Yoko Ono in 1969, they staged a “Bed-In for Peace” at the Amsterdam Hilton. Later that year, at their second “Bed-In,” they recorded “Give Peace a Chance” along with several celebrities, including Tommy Smothers, Timothy Leary, Petula Clark, Dick Gregory, and Murray the K. Later, in October of 1969, in Washington D.C. a half million Vietnam War protestors sang the song at the Second Vietnam Moratorium.

In 1971 after moving to New York, John and Yoko became friends with Abbie Hoffman and Jerry Rubin, who co-founded the Youth International Party, also known as the “Yippies,” who staged a series of elaborate anti-war rallies and demonstrations over the course of the next few years along with the support of John and Yoko. The Nixon administration considered him a serious threat to his reelection in 1972 as they believed he could mobilize the youth vote against Nixon as well as donate sizeable sums of money for rallies that would disrupt Nixon’s idea of an orderly America. As a result, in March of 1972, the Immigration and Naturalization Service began a four-year effort to deport Lennon based on his 1968 conviction of drug possession. It was not until 1975, after Richard Nixon’s resignation, that a deportation order was overturned, and the next year he was finally given his “green card.”

I think it appropriate this time of year to revisit John and Yoko’s anti-war campaign of late 1969, at which time they rented billboards in eleven cities around the world which read: “WAR IS OVER! (If You Want It) Happy Christmas from John and Yoko“. The cities involved were Amsterdam, Athens, Berlin, Helsinki, Hong Kong, London, Los Angeles, New York, Paris, Rome, Tokyo, and Toronto. This was followed up in October of 1971 with the recording of “Happy Xmas (War is Over)” and the video you see below. The Harlem Community Choir provides the backup of children’s voices and is credited on the single.

As was noted by Stephen Holden in Rolling Stone Magazine, John Lennon was a man who “personalized the political and politicized the personal, often making the two stances interchangeable but sometimes ripping out the seams altogether.” He went on to write that “John Lennon believed passionately that popular music could and should do more than merely entertain, and by acting out this conviction, he changed the face of rock & roll forever.”

John Lennon is a man who has inspired me for the greater part of four decades, and this Christmas, I salute his memory while at the same time noting that his words and deeds are every bit as relevant today as they were 32 years ago, “The Day the Music Died.”

You must be logged in to post a comment Login