Likening domestic violence convictions to traffic offenses, Justice Thomas defends offenders easy access to guns.

The Supreme Court handed down three opinions on Monday: one a landmark case handing pro-choice advocates the biggest Supreme Court victory on abortion in decades; another opinion overturning former Virginia governor Robert F. McDonnell’s public-corruption conviction and “imposing higher standards for federal prosecutors who charge public officials with wrongdoing;” and a third opinion holding that a federal “law prohibiting gun ownership does extend to individuals convicted of reckless domestic assault.”

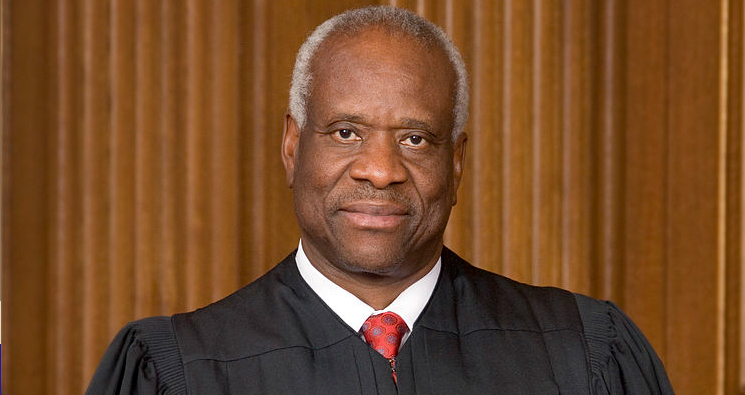

As PolicyMic reports that “In February, the Voisine v. the United States case moved Justice Clarence Thomas, famously silent, to ask his first question during oral arguments in 10 years. “

At the time, he asked U.S. Assistant to the Solicitor General Ilana Eisenstein whether “recklessness” is reason enough to warrant a “lifetime ban on possession of a gun, which, at least as of now, is a constitutional right.”

“Give me another area where a misdemeanor violation suspends a constitutional right,” he asked, later suggesting that the convicted domestic abusers in this particular case should not lose their ability to carry guns because they never actually “used a weapon against a family member.”

Justice Kagan delivered the 6-2 opinion of the court on Monday explaining that: “the federal ban on firearms possession applies to any person with a prior misdemeanor conviction for the ‘use… of physical force’ against a domestic relation. That language, naturally read, encompasses acts of force undertaken recklessly – i.e., with conscious disregard of a substantial risk of harm.”

As Reason reports: “Writing in dissent, Justice Clarence Thomas, joined by Justice Sonia Sotomayor, rejected the majority’s ‘overly broad conception of a use of force.’ In the Thomas-Sotomayor view, ‘the majority blurs the distinction between recklessness and intentional wrongdoing’ and thereby does a grave injustice to criminal defendants.”

In his dissent, Thomas writes that the law prohibiting gun ownership based on misdemeanor assault “is already overly broad;” Thomas goes on to claim that the law could divest others – such as mothers disciplining their children – of the Second Amendment right to bear arms.

Writing of the particular statute in question – Section 922(g)(9) – Thomas writes that the law “is already very broad.”

It imposes a lifetime ban on gun ownership for a single intentional nonconsensual touching of a family member. A mother who slaps her 18-year-old son for talking back to her—an intentional use of force—could lose her right to bear arms forever if she is cited by the police under a local ordinance. The majority seeks to expand that already broad rule to any reckless physical injury or nonconsensual touch. I would not extend the statute into that constitutionally problematic territory.

Thomas goes on to complain that this law could impose a “lifetime ban” for “all non-felony domestic offenses,” likening them to other summary offenses, such as receiving traffic citations:

Section 922(g)(9) does far more than “close [a] dangerous loophole” by prohibiting individuals who had committed felony domestic violence from possessing guns simply because they pleaded guilty to misdemeanors. It imposes a lifetime ban on possessing a gun for all non-felony domestic offenses, including so-called infractions or summary offenses. These infractions, like traffic tickets, are so minor that individuals do not have a right to trial by jury.

Continuing the analogy, he writes: “Under the majority’s reading, a single conviction under a state assault statute for recklessly causing an injury to a family member—such as by texting while driving—can now trigger a lifetime ban on gun ownership.”

Complaining that “the Court continues to ‘relegat[e] the Second Amendment to a second-class right,” Thomas concludes his dissent – writing:

In enacting §922(g)(9), Congress was not worried about a husband dropping a plate on his wife’s foot or a parent injuring her child by texting while driving. Congress was worried that family members were abusing other family members through acts of violence and keeping their guns by pleading down to misdemeanors. Prohibiting those convicted of intentional and knowing batteries from pos- sessing guns—but not those convicted of reckless batter- ies—amply carries out Congress’ objective.

Instead, under the majority’s approach, a parent who has a car accident because he sent a text message while driving can lose his right to bear arms forever if his wife or child suffers the slightest injury from the crash. This is obviously not the correct reading of §922(g)(9). The “use of physical force” does not include crimes involving purely reckless conduct. Because Maine’s statute punishes such conduct, it sweeps more broadly than the “use of physical force.” I respectfully dissent.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login