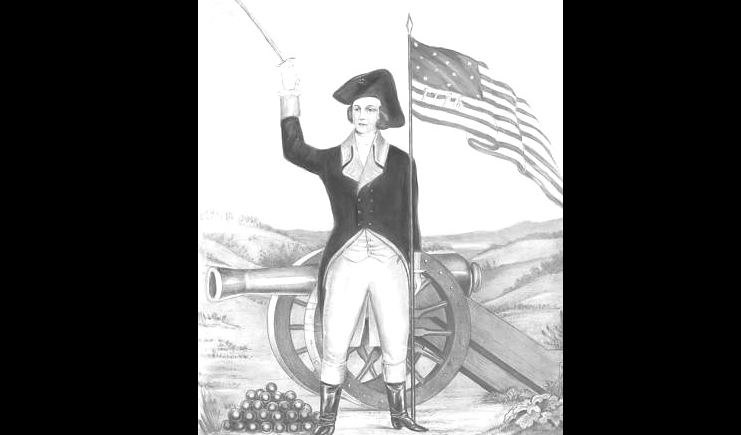

Deborah Sampson posed as a man to fight in the Revolutionary War.

Human beings are made up of all kinds of people who have all kinds of interests and desires. Sometimes the law dictates that only one gender—usually male—or one race is permitted to engage in a given activity or cause. These biases can and will be overcome when someone finally has had enough!

Take for example, Deborah Sampson. She wanted to be a soldier and fight during the American Revolutionary War. In 1778 women weren’t permitted to enlist in the military. Sampson was against British rule and she wanted to fight, so she joined the Continental Army disguised as a man.

She fought under the name of Robert Shurtliff (her deceased brother’s first and middle name) and she served for seventeen months. Because she was 5’7 and considered tall, it was quite easy for her to convince people she was a man. She was teased by other soldiers for not having to shave, but clearly, she was able to fool the masses.

She was chosen for the Light Infantry Company of the 4th Massachusetts Regiment under the command of Captain George Webb, and the unit was made up of approximately fifty to sixty men.

Sampson was wounded during her first battle on July 3, 1782 outside of Tarrytown, New York — receiving two musket balls in her thighs and a huge cut on her forehead. Afraid she would be discovered, she begged fellow soldiers to leave her to die. Despite her pleading, they refused to abandon her and took her to the hospital where she was treated for her head wound. Before doctors had an opportunity to tend to the musket balls, she left the hospital and removed one of the balls from her thigh by herself with a penknife and sewing needle. Her leg never fully healed because the second musket ball was lodged too deep into her thigh for her to remove.

Everyone assumed the war was over when the peace treaty was signed, but on June 24, General Washington was ordered by the President of Congress to send a fleet of soldiers to Philadelphia to “aid in squelching a rebellion of several American officers.” Just as this was happening, Sampson fell ill with a fever. The doctor who treated her removed her clothes and her secret was out. Fortunately, he did not reveal the fact she was a woman posing as a man — in fact, he took her to his home and treated her with the help of his wife and daughters.

When Sampson recovered, she returned to the army for a brief time. In September of 1783, the Treaty of Paris was signed and peace was assured. When the doctor who treated her asked her to deliver a note to General John Paterson revealing her gender. She thought Paterson would expose her secret—fortunately for her, he did not. Sampson was granted an honorable discharge by Henry Knox after a year and a half of service, with a note with some words of advice and only enough money to pay for her trip home.

Eight years later in January 1792, her story became known when she petitioned Massachusetts State Legislature for the earnings withheld as a result of her being a woman. With the help of her friend Paul Revere, her petition was approved and signed by Governor John Hancock. The General Court of Massachusetts verified her service and wrote that she “exhibited an extraordinary instance of female heroism by discharging the duties of a faithful gallant soldier, and at the same time preserving the virtue and chastity of her gender, unsuspected and unblemished.” She was awarded 34 pounds—which was considered quite inadequate and ultimately resulted in Sampson giving lectures for profit, discussing her wartime experiences.

Because of her extraordinary achievements and bravery, her successful struggle for the American Revolutionary War pension bridged the gender gap in asserting that all veterans who fought for their country were entitled to compensation.

In Sharon, Massachusetts, a statue was erected in front of the library honoring Sampson. Sharon also has Deborah Sampson Street, Deborah Sampson Field and the Deborah Sampson House.

Excerpt from Women in the U.S. Army, courtesy of www.army.mil:

“…in February 1946, Army Chief of Staff Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower directed the preparation of legislation to make the Women’s Army Corps a permanent part of the Army. Lt. Col. Mary Louise Milligan (later Rasmuson) became a consultant/planner for the project. Col. Hallaren, third director of the WAC, became the recognized leader in the fight for passage of the legislation. In September 1947, the bill was combined with the WAVES/Women Marines bill and a section to include women in the Air Force was added. The bill was renamed the Women’s Armed Services Integration Act. President Truman signed the bill into law on June 12, 1948.

In July 1948, the first enlisted women entered the Regular Army and in December, the first WAC officers received Regular Army appointments. Women could enlist from ages 18 to 35. Enlistment under age 21 required parental or guardian consent. Women were no longer sent to a TO unit of 150 women, but received individual assignments. Enlistments in the Women’s Army Corps, Regular Army, opened to civilians in September 1948, and on Oct. 4, the Women’s Army Corps Training Center opened at Camp Lee, Va.”

As women, we have to fight harder for our rights and freedoms. It’s important to never forget the risks and the actions of our foremothers so that we can build on what has already been achieved.

Like Kimberley A. Johnson on Facebook HERE, follow her HERE. Twitter: @authorkimberley

Listen to her podcasts on iTunes and Patreon.

You must be logged in to post a comment Login